I just watched

’s new video on the Protestant Work Ethic. This is the idea that we in many Western countries, but focused mainly on America, have created the moral obligation to work, and we have lost the ability to live outside of work. It is a good video that is worth watching, but there are some areas that were stretched to fit the conclusion he was seeking. The way we discuss work and leisure now is incompatible with how it was discussed in Greece—or even America two hundred years ago. The religious discussion, especially surrounding Puritans and Calvinism, is also lacking, and there is a larger phenomenon that is missing from this entirely.I’m not a philosopher, nor have I read nearly as deeply on this specific topic as Henderson has, but I have observed how work is talked about in the modern world. I also know that definitions are important for clarity. For this piece, I will define work and leisure in the following ways:

Work is not just a job, it is associating any activity one does with some expected output, whether that's dictated by her or someone else. That output doesn’t need to be monetary, it could be achieving some specific fitness goal, or even learning how to like a certain genre of film. These are tasks that require focus, attention, and retention.

Leisure on the other hand is doing something that one finds fun or relaxing with no expectations outside of enjoyment. They are activities that are done to take a break from work. This could be reading or watching a movie he knows he will like, or getting a coffee with a friend, or journaling. There is no audience to please and no expectation of progress.

Henderson makes the argument, and I agree, that these have become a bit blurred in the age of influencers, Booktok, Etsy shop owners, and podcasts. Activities that were seen as pure leisure, except for those comparative few who participated in craft fairs and farmers markets, are now seen as side hustles1. Furthermore, this idea of work—and the inherent need for progress—has invaded every aspect of life beyond just the monetizable. We set goals and track the amount of books we read, our workouts, and our sleep, and even our eating has become a game of chasing macros. But, this is where my agreement ends. The way we think about work has changed not because of the culture, but because the work itself has changed.

How Work has Changed

Henderson talks about the Ancient Greek view of work as a “curse.” To the men of Athens, work was meant to be avoided. He says that less work would allow for more time to spend in “action, politics, and philosophy.” He continues on to say that the view of work has shifted from something to be avoided to the thing that gives meaning to life. That is true to an extent, but today, even politics and philosophy are now considered work. Furthermore, the nature of the work itself has changed since then, especially recently, and cannot be ignored.

Henderson states that the reason Athenian men could avoid work was because of the slaves doing the work for them, that is a point that should not be glossed over. There was a similar phenomenon in colonial America where the richest landowners were able to live lives of pure leisure—and focus on buying the latest new fashion as I have discussed—while their slaves and servants toiled in the fields. The middle class artisans, on the other hand, tried their best, but mostly failed, to achieve that same freedom. In short, it was a luxury to have lots of leisure time, much like it was in Athens, due to the major class divide.

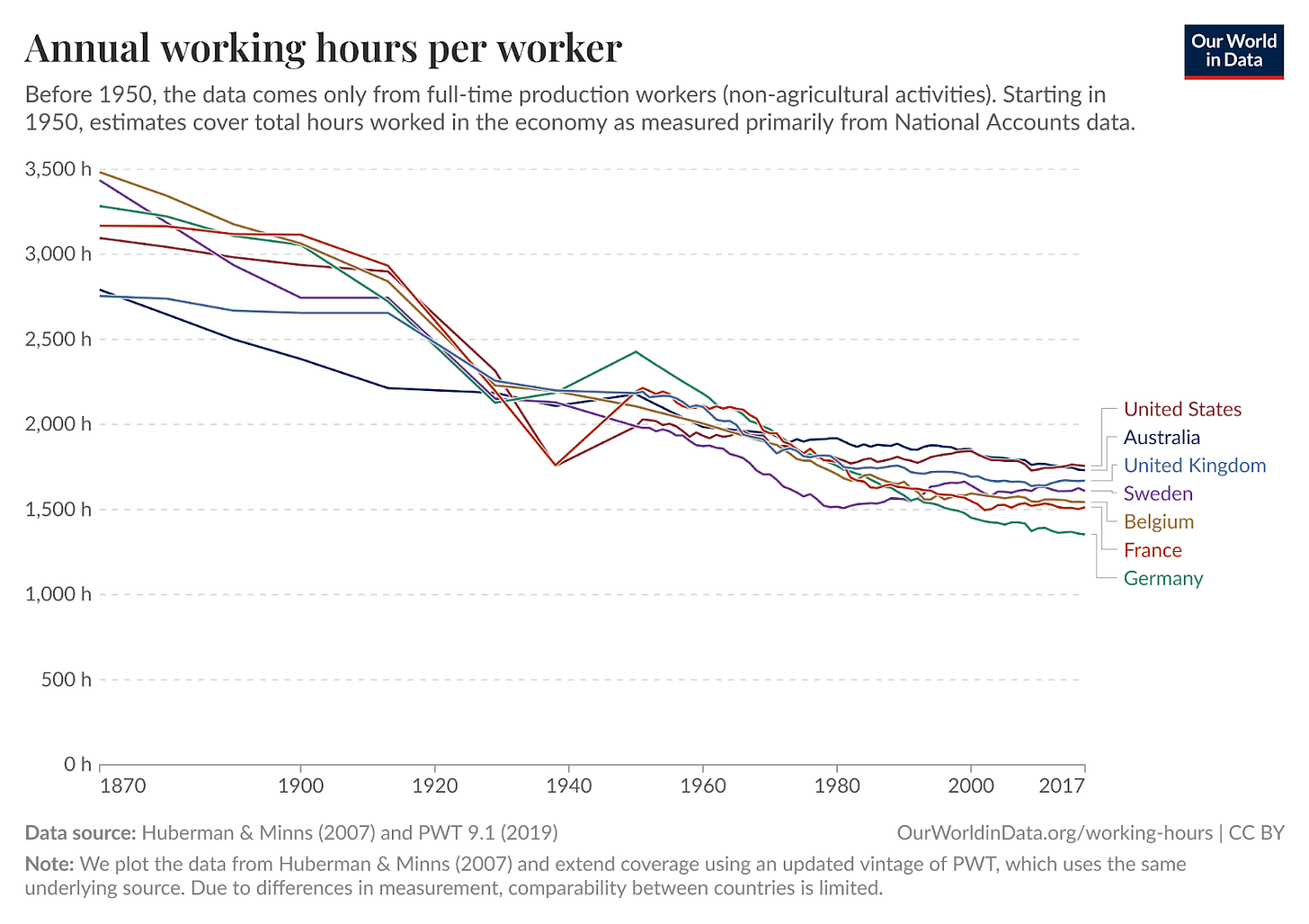

I am not one to argue that this class distinction exists in the same way today. I think it does history a disservice to do so. People now have far more time for leisure2, generally, than even 100 years ago, let alone 250 or 2000. Whether they are actually using that time for that purpose is a different story, and one I will discuss later. The work done by the middle and working class is now very different from 1750. We have a far more service focused economy than ever before; about 20% of our jobs today are manufacturing or resource extraction. We are far less agrarian, and our manufacturing is much more specialized, and far less localized. As we have become far more integrated globally as an economy, we no longer need to do as much labor for our own safety, or health. I’m not going to go into a deep dive with this, but put shortly: gardening is no longer necessarily work, and reading and writing about philosophy is no longer necessarily leisure.

I don’t know if Henderson has ever addressed “bullshit jobs,” but that idea has some overlap with his concerns for the amount of work we do. So much of our work is now unfulfilling because we do not often see the end result of the work. Not all work can provide meaning or be a moral good, so we need to re-evaluate what we consider work. A soulless office job is just as much “work” as learning a new skill or raising a child is. But while the latter two provide fulfillment, the former is merely a means to financial ends. Both are work, but I don’t think many are as worried about learning new skills3—despite the numerous digs at productivity bros—as they are about the daily corporate grind. I’d argue both fit within the mold of the Protestant Work Ethic presented.

The Puritan Ethic

The name of the phenomenon, Protestant Work Ethic, requires a dive into the Reformation and the role of religion in America over time. Henderson does state that both Luther and Calvin held strongly the doctrine of predestination. But the problem is, all Christians hold that doctrine. There is some debate about who exactly is predestined to go to Heaven, but it is a core principle of Christianity. Luther stated that salvation is given to those who seek God. Calvin, on the other hand, believed that just a few are “elected” to go to heaven and all else are predestined to go to Hell, a departure from the others.

In the American context, the Puritans, devoutly and militantly Calvinist, held the view that only a select few were chosen. Henderson states that wealth was a sign of the elect being chosen for heaven. This may have been true, but Calvinists—more specifically Puritans—did not use work to try to reach those riches. This would have constituted living by the covenant of works—the idea that earthly deeds will help one go to Heaven—and antithetical to the Puritan ideal of a covenant of grace—that those going to Heaven were chosen by God. In 1636, this debate was held publicly when Anne Hutchinson accused the Boston ministers of preaching a covenant of works. For this outlandish accusation, and for having her own sermon as a woman, she was banished from Massachusetts and excommunicated from the Boston Church.

The Puritans were not the type to work for any sort of moral reason, as can be plainly seen. The role of religion also changed throughout America’s history, with two major revivals and the more recent rapid secularization. Within fifty years of the first Puritan settlements, the church population was already diluted with the acceptance of non-Elect, and other denominations, including Catholicism, had just as much participation throughout the colonial world. So it would be hard to trace the work ethic of Americans today to any singular religious sect, especially one as small today as Calvinism. There are far too many historical and economic factors to tie our way of working to a single doctrine.

This is only further muddied when we look at global data. There is a small correlation between predominantly Protestant versus predominantly Roman Catholic countries in the West, but it is clear that religion is the actual underlying cause. What I do notice is a cluster of nations that were once colonies of Great Britain. There may actually be an Anglican Work Ethic. But, that is an oversimplification as well. To my eye, there is more correlation with culture than religion, and even more correlation with the level of industrialization. But, it’s just as likely that none of these are correlated, or they all are to a certain extent.

In short, the link between Protestantism and the way we work today is not as clearly linked as Henderson lays out. There are other cultural and economic factors that play just as big of a role as religion. Likewise, the US does not represent either extreme of overwork or lack of leisure, so looking just at our history leaves a lot out of the frame. But, even with that being the case, there is still a feeling of unease with American working life. We do have an unhealthy relationship with work. I think there is an unexplored aspect of the work-leisure balance that is at the heart of the issue and why there is so much talk about burnout—we aren’t actually doing either properly.

The Inbetweentime

The biggest issue when discussing our relationship with work, especially within the past few years, is not that we work too much. Rather, it is our inability to separate work and leisure time. As a society, we don’t allow ourselves to fully commit to one or the other. We listen to podcasts when we do household chores or do menial tasks for our jobs, and, as I stated before, we track every bit of our leisure time to reach goals we set. Our work is mixed with leisure activities, and our leisure feels like work. We are simultaneously emptying and filling our cup, and not getting the real benefit of either mode. I think this is the true cause for the guilt that Henderson describes.

I have realized in my own life that when I am in between work and leisure, I am the most unsettled. That is, I am not working at my job or any other project that I have an expected output for, nor am I actually doing a relaxing activity free from expectation like watching a movie or reading a book. This in-between zone I get stuck in is most often associated with sitting on my phone. I’m watching YouTube videos, reading Substack articles, or getting news updates. In short, I am "learning" and "relaxing" but never fully engaged in either activity for it to have an effect. In the end, I feel guilty not because I didn’t work, but because I didn’t make a choice.

As a thought experiment, which of the following lives seems more worthwhile:

Frank works at his office job with a podcast or audiobook playing for much of the day. He struggles to maintain focus because he is trying to listen to the exciting content and figure out the best way to analyze the data he was just given. When he gets home, he orders something on DoorDash, throws on the latest show on Netflix, and scrolls through Twitter until it’s time to go to sleep.

Paul works at his office job with either no music, or something that he’s heard a thousand times. He chats with his coworkers every hour or so about life, the weather, or the game. During his lunch break, he sneaks in some reading of the articles he saved on his phone. When he gets home, he listens to a podcast while he makes dinner, scrolls a bit as he eats, and watches an episode of that new show before he reads a bit in bed.

In these two scenarios, they both are at work for the same amount of hours. They both get distracted, but Paul is able to get more focused hours than Frank. Frank is able to ingest far more leisurely content every day. He probably could get through an audiobook every couple days, unless it’s the latest Brandon Sanderson release, makes far faster progress with the new shows, and likely is up-to-date on most of the latest news. But does it really seem better than the second scenario?

There is intentionality built into Paul’s routine. Sure, he listens to a podcast while he cooks or scrolls on his phone as he eats, but neither are as pervasive as the endless podcast noise. By allowing himself to be in one mode or the other, as best as possible in our increasingly distracted world, he likely gets more work actually completed and feels more fulfilled by the content he ingests.

So, we may have more leisure time than before, but this in-between time keeps us from utilizing it properly. We are not refilling our energy outside of work as we should be. Nor are we utilizing our work time properly. We lack focus and our output suffers because of it. I do think work is a moral good, not because of any religious doctrine, but for the same reason Henderson states in the video: because it is fulfilling to do meaningful work. Perhaps this meaning cannot be found in most jobs today. But, by never committing to either work or leisure we are just burning out faster, making it harder to focus on the work that does have meaning to us.

Conclusion

I think this article can be seen as a more coherent addendum to my last essay, which got away from me, I will admit. I think we will be better off as a generation of people if we learn how to distinguish work and leisure. We will get more done and be more relaxed as a result. By all means, work on personal projects as a way to escape the doldrums of corporate life. But not everything needs to have the same level of utility. You can work out for 15 minutes if you're not feeling up for a full routine, dive deep into a single book for a month, crochet a hat for yourself. It’s also fine to listen to an audiobook while you workout. But don’t beat yourself up when you miss a day of either activity.

The problem isn’t necessarily that Americans work too much in our capitalist system, nor is it that we are bound to the religious doctrine that no longer fits our society. The issue is that we are not intentional enough about work or leisure, and are worse off because of it. This intentionality will help us escape the in-between space where so many of us reside in; the in-between that is likely causing the rise in anxiety. We won’t be able to reach the heights of the historical figures that broke through the anxious era they lived through and brought something new to the table. Alexander Hamilton wasn’t listening to a podcast when he wrote the Federalist Papers, and Lincoln wasn’t scrolling on his phone when he was preparing for his debates with Stephen Douglas. We need time to think deeply and time to relax and recover.

The modern world requires our constant engagement to ensure we don’t miss anything, no matter how mundane. Being intenitional with our time will allow us to appreciate, and create, the beauty in the world.

I will admit my podcast is my attempt at a long term replacement for my regular 9-5. Though, I also have very little time to devote to writing as much as platforms like Substack prefer, so I'm in it for the long haul.

Henderson also makes note of the predictions that we would be working 15-20 hours a week. These predictions, like those of Keynes in 1930 and William Morris in 1884, occurred during a massive downswing in hours worked per year. Perhaps there predictions were based on faulty initial conditions. I’d also argue—and Henderson would likely agree—that most people are not actively working for 40 or more hours a week like they would have been in the factories at the turn of the 20th century. So even if they are at a job for 40 hours, many are working far fewer hours, and if they were more intentional, could work even less.

There is still some risk of burnout when trying to learn to many skills at once. But, in this instance I mean one at a time.