Against Catastrophism

Are we going to squander this moment with our pessimism?

Can you feel it? The vibe shift? It’s clear to anyone paying attention. The fascist takeover of the American government has come. Or the economy is being manipulated to keep us little guys down. Or America has been here before and is on the precipice of something great. There have been anxious periods in our history, and not all of them had bad outcomes. Perhaps the catastophizers could read some more history before making such bold predictions.

Trump’s second victory has caused whiplash to the American political world with the flurry of Executive Orders and agency shakeups and shakedowns. This is noteworthy, to be sure, but this shift in the political and cultural winds has brought out the pundit in us all. With this constant whirlwind of major developments, I have been largely left behind, even with my relatively high level of political media consumption. From what I have been able to grasp, I have noticed that there has been a shift in political discussion—especially here on Substack—that has been becoming more and more abrasive.

Everyone has some prognostication about what this victory means for the future—let me double-check—FIVE WEEKS into a 208-week term1. This usually comes with endless jargon about the “new oligarchy,” or the “end of the neoliberal world order,” or some other ten dollar phrase pulled from history that mean little to the person using them and even less–while being so vague that they can mean anything–to the reader. It’s exhausting to parse through. This is on top of the already endless recycling of complaints about American consumer culture, lazy—read woke—art, economic anxiety, and AI dystopia. The pessimism and cynicism drives me insane, and it takes everything in my will to stop myself from responding to every single one with some variation of “prove it!”

I think what is happening here is twofold. There has been a sense of general malaise since the dreaded year of 2020. The economy, people’s psyches, and ultimately the American social fabric were on the ropes that year. Some of this has recovered, in certain ways, since then, but it still is a strange transitional period. The economy, while still hurting from the intense inflationary period, is technically recovering and the social fabric, while strained, has allowed for moments like Barbenheimer or the Eras Tour to bring us closer together. As for people’s psyches, I’ll leave that to Jonathan Haidt to parse. But it feels as if we have never left that era of our personal and political lives becoming blurred due to the digitization of our entire lives. We are no longer allowing the world to settle after that intense shock of the pandemic. They are just Tweeting—or Notes-ing?—through it.

The other aspect of this is how many people want something to happen. More specifically, they want something that has happened before to happen again. They want to be the ones fighting alongside the modern day Martin Luther King Jr. This used to be localized to the left hoping for a new Civil Rights Movement to glom on to, but it has infected the right recently. People on the left got that moment in June 2020, but quickly overstayed their welcome, so much so that by November 2024, the right has their moment. That is where we are at now. Maybe I'm falling into the "nothing ever happens" trope, but I don’t think either will get what they want in the end.

So when people talk about capitalism or globalism, they are just cosplaying as someone who cares. Someone on the “right side of history,” whatever that means to them. They are the tide shifting force that will bring about a new era of American politics. But, they complain about the evils of capitalism from their iPhones, or the dangers of globalism from their brand-new PC with the latest NVIDIA graphics card, agreeing only that the problem with American society is how easy it is to get stuff. Stuff they might not want or need, but is readily available from a single click, new stuff that is always beckoning them. There is nothing good to come from the world we live in today, nor are the drawbacks due to their own impulse control. It’s all so tiresome.

Look, I have some qualms with the current state of overconsumption and mass consumerism2. I don’t like mugs that look homemade but are mass-produced, nor do I like the idea of being forced to buy new rather than be able to fix old. I understand that I have lived my whole life in a massively globalized, liberal world so I really have nothing to compare it to. But I think we do live in a different world than a few decades ago when you could look at your neighbor and sneer at their Chevy, or marvel at their new flat screen, or help them fix their dishwasher. Now the Chevys look like Mercedes, but with more plastic and fewer screens, there’s a flat screen in every room, and dishwashers require apps to function. On the other hand, we also have more ability to learn anything at our fingertips than any previous generation had in their library3, and we don’t die from Polio. But when we actually look at these two different worlds, are they actually that different in the end.

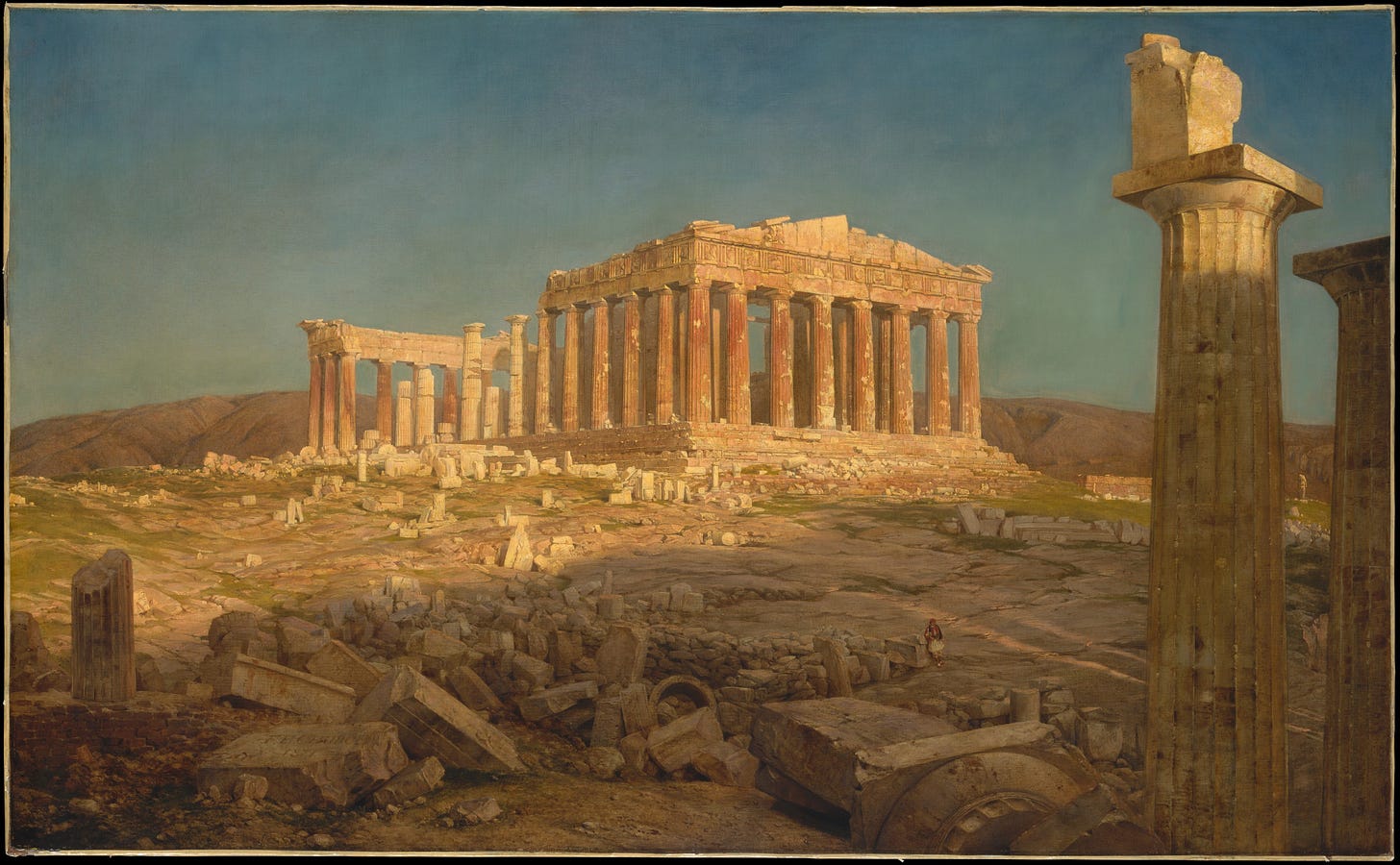

Regardless of which seems better for the mind, body, and soul, both worlds play off of one aspect of American society that seems to be a mainstay from even before this continent had a country of that name. Consumerism, keeping-up-with-the-Joneses, the haves and the have-nots are not new phenomena. We are just living through an era in which they seem to be more heavily pronounced. An era where these ideas seem to increasingly occupy our waking minds. Yes, social media is to blame for some of this, that is not debatable. However, there have been times in America’s past that were just like this. Times with massive debts, societal anxiety, and malaise recovery. To these internet prognosticators, I’m sure it seems like this era we live in is just the precursor to another Great Depression—or if they collect a different set of facts, a communist revolution. Perhaps it is. I can’t read the future as well as anyone else. But it could be the beginning of something far more positive, the precursor to the birth of a new culture, economy, and politics.

The American colonists in the middle of the 18th century faced a similarly materialistic world as we do today. The haves controlled vast amounts of land—and more land meant more power. They had grand estates where they hosted lavish parties to show off their new fineries. They would mock and sneer at their neighbors who did not have the latest Georgian furniture, or silken threads. The lower classes tried their best to emulate the latest fashion of the rich, usually by buying a single piece or two that looked the part, but were never able to afford the real thing. They would go to the local tavern for their simple get-togethers, and dream for more. This attempt at rising in class would elicit evermore mocking from the rich.

We can see individuals who pitied these attempts to break from their rank. People like Dr. Alexander Hamilton, during a tour of his home colony of Maryland in 1744, maligned those colonists who had “fine goods displayed in otherwise common dwellings. At one farm, he found ‘superfluous things which showed an inclination to finery … such as a looking glass with a painted frame, half a dozen pewter spoons and as many plates … a set of stone tea dishes, and a teapot.’”4 He felt it was the duty of these people to use the implements that fit their class, like wooden spoons, and water buckets as mirrors. All he saw in them was blind aspiration for a world that they would never be part of. In today’s parlance, they were “temporarily embarrassed billionaires.”

But, Hamilton was part of a new gentile class that emerged during the economic boom that took place in the middle of the eighteenth century, a time of relative peace in the colonies, and laxity in trade enforcement. Imports rose some 50 percent from 1720 to 1770, and the new rich in the American colonies began to emulate the gentry in England. They adopted new styles of dress, new manners, and new ways of talking. From their estates, “every action, every statement, every object was on display and subject to applause or censure. The well-trained eye and ear scrutinized details for the proper nuances of fashion. A faulty performance damned the unfortunate as impostors, as ridiculous as clowns.” Just as the middle class strived to joining this new elite, these elites were striving to join the English gentry. By the time of the revolution, they actually began to reach their sought after status, unlike most of the ambitious artisans. But to do so, they racked up incredible debts.

It is easy to argue that it is different today, with the nearly ubiquitous nature of Amazon delivery allowing us to buy new gadgets within seconds and receive them within days, if not hours. But, that is more a difference of scale than a difference in kind. Debt is much easier to come by nowadays with credit cards and car loans, and ads inundate every part of our minds whether we’re conscious of them or not. But we need to stop pretending that debt is new, or that the middle class of yore was some bastion of freedom from hierarchical structures and financial burdens. America from before it's founding was built on debt. It became extremely wealthy, even compared to the head of the empire it was part of, because of that debt. This is nothing new. Yes, there is a rapid change in cost of living that has shocked our system. Everything being 20—or more—percent higher than it was 5 years ago is an issue. But we don’t live in unprecedented times. These colonists also had memories of their fathers and grandfathers fighting in the wars between England, France, Spain, and the Indians. Many lived through the last war. The malaise we feel today is real, but if our forebears can deal with the decades long threat of war displacing or killing them and come out stronger afterward, we can put our phones down long enough to stop the urge to buy the newest Booktok trend. We don’t have to be at the precipice of a new Great Depression, we could be at the precipice of a new American boom.

During the latter half of that half century, America was embroiled in two more imperial wars. Thousands were killed throughout the colonial world as a result. This was just a reminder that the colonies were still beholden to the whims of a far-off king who had very little understanding of life across the Atlantic. It was a messy, chaotic, and fraught time with so much seemingly out of the control of the colonists. But at the same time, a new religious revival swept through the colonies parallel to a rise in secular political philosophy. The works of Jon Edwards and John Locke floated throughout the colonies for decades and influenced men like Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. New ideas for government were floated and when the debts of the empire began to add to the personal debts of the elites, they took matters into their own hands and set the world on a vastly different course than it had been on just a decade earlier.

Just like my last essay, I will add a disclaimer that I am not hoping for a second American Revolution5. You won’t find me calling for war here, and have a pretty good gig going on right now. I also think that replacing the 250 years of development, politically and institutionally, would likely lead to more harm than good, as loath as I am to say it. I’m fine with letting tearing down certain pieces with care, but Chesterton had a point. But I can’t help but feel a sort of unearned nostalgia for this period of time, the pre-Revolution period, when there was so much movement forward as a people, and eventually as a nation. I think it goes hand-in-hand with the optimism I feel towards the future. I have my moments of worry, no doubt, but as a whole, I feel good about our prospects.

So what I hope is that these cynical internet wannabe-pundits start to look at other areas of history and expand the possibilities of what the future may bring after this seemingly dismal present. I could be wrong, I have been wrong before and surely will be again. Perhaps these cynics just know more than me–something I’m sure they are eager to tell me. I have a feeling they are just too pessimistic to let some light shine through.

Americans, historically, are an optimistic people. They don’t care if you call them a temporarily embarrassed billionaire, because the dream, the desire, the hope is what matters. This seems to have been lost recently, and no doubt the feeling of decline stems from that, even if it is not matched by the data6. The feeling of not being able to get a job, get married, have a kid, buy a house. In this economy? In this world? I did those things. Maybe I’m the most privileged man in the world, or pulled a needle out of a haystack while blindfolded. Regardless, America is in a strange place right now, in a transition, just as it has been before, and just as it will again. It will take those that are hopeful for what the future can bring to drag the rest of the country forward. Catastrophism will not do that.

To be fair, it has been three months since the election, so this ramp up wasn’t sudden.

Just look at books, or fashion, or skin care if you want to see this in action. My wife and I, mostly out of an aversion to spending money, have become rather minimalist in these aspects of life compared to the standard set on social media. We still love eating at restaurants, though—we all have our vices.

And yes, I do think that is a good thing. The internet, for all of its flaws–of which there are many, and I suffer from them often–has been a boon to those that seek knowledge, new and old.

Alan Taylor, American Colonies, ed. Eric Foner (New York: Penguin Books, 2001), 353.

Even if we have similar complaints and one could relate the concerns of the Founders and modern Americans, there is still a major difference: we are not the overseas colonial project of a larger empire. We are the empire.

I vacillate between these two and have been trying to square these two realities for over a year now. This post is part of that exploration, which explains why this essay is more confounding than clarifying.

Hi Scott, I enjoyed this episode about people in the colonies improving their standard of living and your comparison to our current situation after the election. I agree with you that we could be at the start of a positive new era in our history. I’m a Baby Boomer and I believe that we are ending an era that started with the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963, and is ending with the election of President Trump. Up until Kennedy was killed most Americans trusted our government, but his assassination started a lot of talk in society about the CIA and the Mafia involvement etc. After years of the civil rights movement congress finally passed the Civil Rights Act & the Voting Rights Act. The Great Society programs were lifting people out of poverty, and we were at war in Vietnam to save the world from Communism. Mainstream religions became more liberal, and people began to reject the Judeo/Christian moral standards. we had riots in cities and on college campuses for the free speech movement and civil rights riots in our cities.Music promoted drugs and “love the one you’re with”. Open sexuality and pornography became mainstream. Everyone was happy. We had thrown off the old fashioned traditions. Average people had good paying manufacturing jobs. What could go wrong. It’s the Age of Aquarius. But by the late 1970’s inflation was high. Manufacturing jobs were moving to Mexico.

By the 1990’s STDs and drug abuse became national problems. In spite of our great technological advances, by the early 2000’s drug addiction was epidemic and homelessness is everywhere. So gradually more & more people began to see that the society was going in the wrong direction, and as you said began to want to go back to save some traditional values. That’s where we are now. The 1960’s Old Guard is fighting to keep their era going by calling their opponents extremist names but that’s not working anymore. So I’m hopeful that as a society we will be going “back to the future.” As a Baby Boomer, I apologize for my generation screwing everything up for the last 60 years.