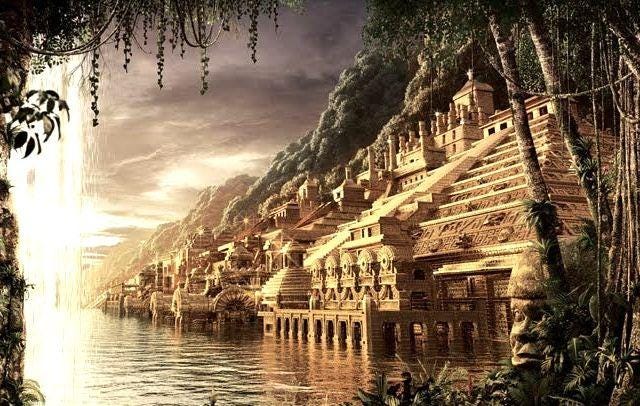

A Search for the Cities of Gold

Travel Log Tuesday #1: The various mythical places the Spanish never found

The exploits of Hernan Cortes shook the world. Those of Fransisco Pizarro upended it completely. Their findings, of empires, of peoples, and, most importantly to the Spanish crown, of gold and silver, ignited the imagination of every wannabe explorer in Spain and beyond. These souls sought the riches and renown that these two men brought themselves when they discovered for the Old World the great empires of the Aztec and the Inca. Little did these newcomers know, just as soon as this gold rush began, it was already over. These two empires were the greatest in the Americas. As they fell, so too did the supply of riches.

But the explorers that came after, like Coronado, the younger Pizarro, and Orellana, did not know that their expeditions were doomed from the start. The lost cities, ancient wonders, and, of course, gold drove these three men to explore the unexplored and relay their discoveries to Europe. None found what they were looking for, but some of the relayed discoveries ignite our sense of wonder today.

The Seven Cities of Cibola

In 1536, the four survivors of the ill-fated Narvaez expedition arrived in Mexico City with tales that rival the best adventure novels. The leader, Cabeza de Vaca, told tales of being stranded on the coast of Florida, travelling the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, surviving sinking rafts, and being enslaved by the Indians. Most importantly, they told stories of giant cities with an abundance of gold, emerald, and turquoise. There was one issue though: no one knew where these cities were. The only survivor who was available to help guide a new expedition led by Marcos de Niza in 1539 was a Moorish slave named Estavenico.

They set out and found the natives extremely forthcoming with information about the cities. Estavenico was sent ahead of the expedition to try to find the cities, and after some time a native scout brought back news of his discoveries. They searched for the city that he had found, but they never found him, whether he was killed or died years later a free man is unknown to us. Before heading home, de Niza climbed a mesa to try to spot anything on the horizon. In the distance, he saw a small set of pueblos shining in the sun, which he assumed was the shine of gold. He rushed back to Mexico City to relate the news of his findings, though much of the details were pulled from his imagination.

These stories spread like wildfire and with each retelling the cities became grander and grander. Eventually, these reports reached the ears of Francisco Vazquez de Coronado. He was the governor of New Galicia and married into a wealthy family. So, he took it upon himself (or his in-laws) to fund another expedition to find the golden cities.

In February 1540, Coronado departed New Spain with some three hundred soldiers, another thousand natives, and de Niza as his guide. They marched until they found the first of the grand cities where Estavenico was supposedly slain. However, there was no city at all, but rather a single village of just a few hundred called Hawikuh. After failed peace negotiations, Coronado marched on the city and took it, slaying or forcefully removing everyone within. It was not an easy battle, but the superior manpower won the day for the Spanish. After raiding all the houses, they found no gold in this village, nor any indication that the real city was nearby. Coronado was incensed with rage and de Niza was quietly sent back to New Spain for his own safety.

The Spanish continued in search of these mythical cities, and even heard rumors of another city of gold, Quivira, further inland. After a full year of marching, killing, and pillaging, they reached Quivira. What they saw was not a city of gold, but a village of nothing more than grass huts. Coronado soon realized his expedition had been based on lies and deceit. He had the man who led him to Quivira strangled and was forced to march back to New Spain a bankrupt failure.

El Dorado

While the Spanish floundered in the North American deserts, a similar search for a city of gold took hold of them in the south. The vast wealth that Fransisco Pizarro had wrestled away from the Inca in 1533 brought forth fantasies of even greater wealth in the Andes mountains and within the bowels of the South American continent. The Spanish heard stories of a ceremony conducted by the Muisca people in the Andes at Lake Guatavita. During the coronation of the new king, he would be placed on a raft, covered in gold dust, and accompanied by gold, treasures, and attendants wearing an abundance of gold jewelry. As the ceremony continued,

accompanied by mass trumpets and singing from the shores, the raft arrived in the very center of the lake. At that moment silence fell on the crowd and the attendants threw the fabulous treasure of gold and jewels into the lake and the people on the shores also threw their golden offerings into the sacred waters. The climax of the ceremony came when the golden king himself leapt into the lake and when he emerged, cleaned of gold, he had become the king of the Muisca.1

In 1636, Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada took eight hundred men into the heart of the Andes mountains in search of this lake. He confronted the Muisca about this king of gold, and after their refusal to submit to Spanish authority, he attacked. After plundering what gold he could from the Muisca, Quesada continued into the mountains despite the treacherous terrain, predatory animals, endless infections, and death.

Though the expeditions were mostly a deadly failure for the Spaniard and the Indians, he, along with his brother, Hernan Perez de Quesada, found Lake Guatavita in a basin deep within the Andes. The brothers attempted to drain the lake to find the gold a few years after this discovery. They formed a chain of bucket men and were able to lower the water level by about ten feet before abandoning the project. A small amount of gold was found in the revealed lakebed, though the excavation was abandoned after just a few months.

In 1641, Gonzalo Pizarro, Francisco Pizarro’s younger brother, decided to conduct an expedition of his own. He gathered over two hundred soldiers and four thousand enslaved Indians and marched over the Andes to reach the Amazon basin. In the rainforest they found an abundance of cinnamon trees, but no signs of a city of gold, despite the forceful, and ultimately deadly, interrogations of some Indians they encountered. Within a year, this expedition was in shambles. To try to revive the expedition, he sent his second in command, Fransisco de Orellana, down river in search of food. On the day after Christmas in 1641, Orellana, and fifty-eight others, left Pizarro behind. Little did either know, the discoveries downriver would have a far greater impact today than a golden city.

The Amazons

After nine days down river, the fifty-nine men on the journey finally found Indians willing to trade food. This society, which Orellana called Omagua, was over six hundred miles downriver. Instead of paddling against the current through a land with no further food, the crew continued downriver hoping to spill out into the Atlantic. To ensure they could justify their change in plan, Friar Carvajal wrote an account of their travels2. Unfortunately for us, looking back almost five centuries later, this log was mostly a justification to protect them from mutiny charges, but what he did write about his surroundings shows a world still unknown to us.

The river was lined with villages filled with hostile people. About halfway through the voyage, he described a society of woman warriors, which he named the Amazons, who reproduced through male sex slaves. As they continued, he wrote that the land became more populous and some sections were “all inhabited, for there was not from village to village a crossbow shot.”3 About four hundred miles from the ocean, some four thousand Indians in about two hundred war canoes approached the Spanish; from the shore hundreds or thousands more watched on. When a cacophony of music rang out from the southern bank, the Indians attacked. Luckily for the Spanish, their gunfire drove the attackers away allowing them to escape. On August 26, 1542, exactly eight months after leaving Pizarro, the Spaniards reached the Atlantic and became the first people known to history to travel the entire length of the Amazon River.

Many of Carvajal’s records are disputed, especially that of the Amazons deep in the rainforest. For centuries afterward, it was assumed that all these stories were fabricated. It was understood by the experts that the Amazon was “the planet’s greatest wilderness, primeval and ancient, an Edenic zone touched by humankind lightly if at all.”4 However, with the discoveries regarding the original Americans, and the staggering influence they had on the ecology of the continents, these assumptions are being challenged.

We know little about the peoples that lived in the Amazon basin. The myriad environments – only about half of the 2.7 million square miles are classified as rainforest – allowed for several different societies to thrive in the center of the continent. It is likely that some were avid agriculturalists, others lived off fishing the river, and some created vast orchards of fruit trees. There was never any city of gold found in the Americas, but these stories bring something even greater to us today.

The Modern City of Gold

The written record of these mythical cities, and the societies that were encountered during the search, provides details of people and cultures that have otherwise been lost to history. Perhaps the Spanish merely misinterpreted the Indians. Perhaps the Indians exaggerated to satisfy their own egos. Perhaps they even lied to bring the gold-hungry Spanish to their enemy’s doorstep. We will likely never know the purpose of these stories.

Regardless, these people were not stupid, they were choosing to tell these tales for a reason. These stories give us a small glimpse into what these people were like, and how they communicated with, or manipulated, those they saw as enemies. Furthermore, it gives some idea into their culture, politics, religion, and myths. Any one of these could have been the reason for these stories of golden cities. But we will never know for sure.

The Spanish lust for gold cost them thousands of lives in these expeditions. Unfortunately, the Indians faced an even greater cost due to the unseen microbes brought across the Atlantic. The immense loss of life from these diseases remains the greatest tragedy the world has ever known. Just like the Spanish before us, we may never find what we’re looking for. But I hope, in an attempt to understand the true extent of this loss to humanity, we never stop looking for our own city of gold.

References

Cartwright, Mark. "El Dorado." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified April 01, 2014. https://www.worldhistory.org/El_Dorado/.

Drye, Willie. The Seven Cities of Cibola, 2024. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/seven-cities-of-cibola.

Grann, David. The lost city of Z: A legendary british explorer’s deadly quest to uncover the secrets of the Amazon. London, England: Simon & Schuster Ltd, 2017.

Mann, Charles C. 1491: New revelations of the Americas before Columbus. New York: Vintage, a division of Random House, Inc, 2011.

Mark, Joshua J.. "Cibola - The Seven Cities of Gold & Coronado." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified May 11, 2021. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1754/cibola---the-seven-cities-of-gold--coronado/.

“Stories: The Mythical Seven Cities of Cíbola.” National Parks Service, June 7, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/coro/learn/historyculture/stories.htm.

Thomson, Keith. Paradise of the damned: The true story of an obsessive quest for El Dorado, the legendary city of gold hardcover. Little Brown and Company, 2024.

Mark Cartwright, “El Dorado,” World History Encyclopedia, October 20, 2024, https://www.worldhistory.org/El_Dorado/.

Pizarro arrived back in Quito six months after the split and immediately called for Orellana’s arrest.

Charles C. Mann, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus (New York: Vintage, a division of Random House, Inc, 2011), 323.

Ibid., 324.