As I make my way through history in Missing Pages, I am not only looking at where American history education lacks. I would also like to determine how historical movements have led to the modern American culture we know today. I have heard people quip that Puritans have a stranglehold on the way Americans act today. It is entirely possible that there are parts of Puritanism that have filtered down to today’s culture. For instance, they had major respect for elders, were private about their sex lives, and perhaps counter to the expected narrative, married later than their peers. But they also had extremely large families, sat through extremely long sermons, and were aggressively against drinking alcohol.

American culture is not easily defined. It does not have strong roots that can be traced back centuries, if not millennia, like some nations boast. Looking at the Puritans alone ignores a large portion, if not the majority, of the population in what is today the United States. The planters of the Chesapeake, the traders in the Middle Colonies, the non-Puritans in New England, and the slaves throughout the colonies all made an impact. Obviously, these were not all English. The Dutch, Swedes, French, Spanish, Irish, and Scottish, and West Africans all made their way, or were brought, to these colonies. Along with groups of people, ideas spread throughout the colonies. Ideas about liberty, the role of government, the hierarchies of society, and racial differences all impact the way our society is shaped today.

I have not found a proper place to discuss all of this at length in the podcast, though I have made references to it. But I want to begin here to chart the journey of the growth of American culture. America as a political entity did not exist for another century after the end of this historical era. However, the ideas that it is based on began to take shape during the 17th century. It was not clear that this would lead to a revolution, even until the years preceding it, but there was a growing sense that this new land was populated by people that were becoming distinct from their European counterparts.

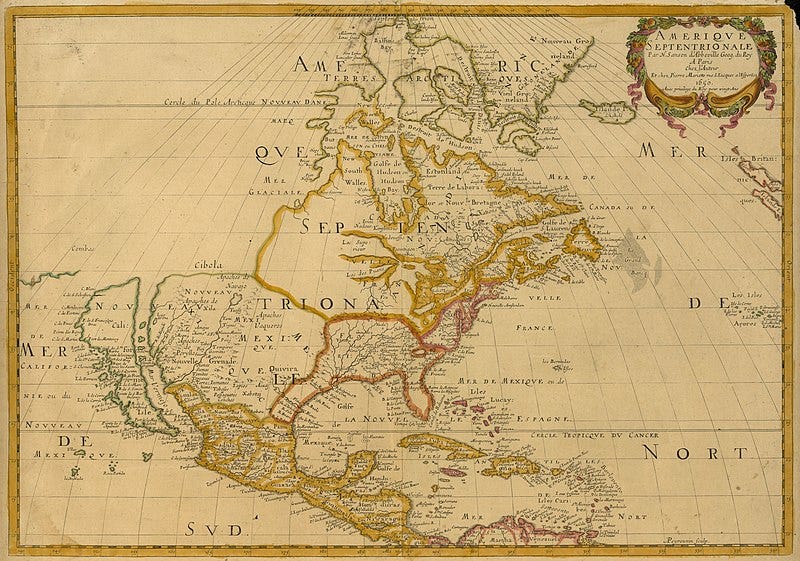

To begin answering this question, and to act as my own mental map, I’d like to conduct a short survey of the different people throughout the colonies at the end of this era. I will attempt to take a snapshot of North American continent in 1675, just before the rebellions that will be discussed in Episode 11 of Missing Pages. I hope that this is the first part of many.

Along the northern coast there were the hardcore Puritans of Massachusetts and Connecticut, with some settlements reaching into Maine. These people were beholden to God and constantly sought his forgiveness. They shied away from sinful delights of drink and free sex. They worshiped their elders and social hierarchies; commitment to conformity was paramount. This was true in religion and in government, where laws were strictly enforced. They worked on fishing boats, felled trees, worked a trade, or provided a service. Many Puritans worked alongside their one or two slaves as well as their many children. They instilled an extreme work ethic in their own lives and proselytized this lifestyle to their kids. They valued education highly and are extremely learned compared to their peers. These values created both a diverse economy and uniform cultural landscape.

The freewheeling, religiously tolerant Rhode Island was nestled between the two Puritan colonies. Created by Roger Williams, a devout Puritan himself, the rabble in the colony, the Quakers, Jews, Indians, pirates, and hucksters often found their way there. The stability of the colony was tenuous internally and externally, but the profound, and novel, ideals of individual freedom and church-state separation had kept the colony from oblivion and reverberate today.

Moving south, the Dutch, more devout to their business than their religion, populated Manhattan and southern Long Island, butting up next to the Puritans to the north. These avid traders and builders brought their business savvy to the New World and spread these ideals from their small home base in New Netherland. Despite the small size and short tenure, the Dutch influence on markets, business structure, and sweet snacks are felt today. The religious liberty and intrepid spirit allowed for a bustling, and often chaotic, port town to thrive. This was not without its struggles for governmental control and piracy, but neither of these held the colony from gaining prominence. Even after the English took over the fort in 1664 during the Second Anglo-Dutch War the Dutch influence remained and the traders on Wall Street feel that influence today, even down to the street name.

Interspersed among these colonies were the Quakers. These devoutly religious people were staunch pacifists and lived simple lives. They were early proponents for true equality, as we see it today, rather than the equality only for those that look or think alike. At this point, they did not have a colony of their own, but the work of William Penn would soon grant them land of their own to build their own society.

Moving south yet again, Maryland’s borders are crossed. The northernmost Chesapeake colony, originally a refuge for Catholics during the height of Puritan domination in England, hosted a diverse religious cadre of largely loyal subjects to the king. The strict hierarchy that existed from manorial estates down to the slaves worked to generate one thing: profits. Like its larger brother to the south this came mainly from one place: tobacco. Tobacco planting took complete hold of the Chesapeake colonies after its adoption soon after Jamestown was first settled. By the 1670s, the economy was nearly entirely dependent on this export. The labor necessary to cultivate these fields enticed the adoption of slavery to slowly supersede the long-lasting institution of indentured servitude. Class divisions that emerged from the headright system made way for race politics. Servants and slaves, though sharing a similar plight, were divided against each other.

The burgeoning Carolina colony to the south brought with it a far expanded use of slave labor. The failed Barbadian planters hoped that these pastures proved to be a little bit greener. The planters decided to cultivate rice, rather than tobacco, to utilize their slaves’ own planting knowledge to their benefit. These large plantations imported from the Caribbean islands led to continuous mass suffering. This feudal like society, like the Chesapeake colonies to the north, enforced a strictly stratified workforce, with the slaves at the bottom took on almost all the burden.

Reaching the southern extent of the coast, the Spanish missions in La Florida were slowly failing. The natives in the region fled the Spanish, succumbed to their diseases, or rebelled. The conversion attempts failed time after time, and eventually were largely abandoned. The recent conflict with several tribes sent on behalf of the Carolinians made this even harder. St. Augustine remained, but further expansions seemed fruitless. Thousands of miles to the west, it was not so fruitless. The land was marked not with trading posts, but with missions. The Spanish spread Catholicism throughout the western part of the continent, though not without resistance. The Franciscans were especially brutal and sold many resistant Indians into slavery. It was only a matter of time before it broke out into a brutal conflict.

Coming down the Mississippi River to threaten the Spanish holdings were the French. The French stayed mostly along the St. Lawrence River in Canada and Acadia. Though after gaining some stability the most intrepid French settlers had started to branch out further west and south. They expanded down towards the Great Lakes and began to make their way down the Mississippi river. The northern forests were pock-marked, not with missions, but with many small trading outposts along the rivers. The intrepid coureur de bois lived among the natives and traded for their furs. They intermarried and adopted local customs; they dressed, ate, and spoke like those that brought them in. Those that remained close to the cities farmed and fished, but the fur trade reigned supreme, the French monopoly on the trade made it by far the most lucrative industry. This trade forced the French to embed themselves with the Iroquois. This brought with it both riches and bloodshed as they were forced to fight other tribes, like the Mohawk, to ensure their trade could continue.

Among all of these people were the Indians that lived on the periphery, only entering the story as a means for war or trade. They're population a tenth of what it was just a century or more ago. They still fought wars amongst themselves for the ever shrinking plot of land. They merged, split, allied, and were destroyed. The life of an Indian during this period is one of anxiety, frustration, heart break, and fury. Their stories may never be fully told, but their existence changed the landscape of the New World. They knew how to use power and how to get what they want. But unfortunately for them, nature had other ideas. Their power in the New World slipped from their hands before they knew it had even happened. In the end they were stuck picking up the scraps and hoping God would grant them the chance for revenge. They would exploit any opening. But they always became the final victims.

Despite this, their cultural heritage was woven into the new American identity. Their farming practices were utilized widely across the East Coast and saved the lives of many settlers. Their ways of war and governance were adopted to help the European settlers to adapt to this new land. It will forever be an unanswerable question as to how different America would look today, had the specter of disease had not been aboard those ships.

Just a few years after this survey, the English colonial world as described above would be torn asunder after a pair of rebellions. The French were facing down an imminent attack by the Onondagas and the Pueblo and Apache would join forces against the Spanish. As if by the flip of a switch, the colonial world would enter a nearly endless international struggle for control of the New World. For the next century alliances would shift, the balance of power would sway to-and-fro, and nations would be wiped off the map.

Despite this, many of the cultural, political, religious, and economic systems that were put into place during the first century and a half of colonization in North America remain with us today. These practices were so ingrained and differentiated from the nations they originated that it had become clear that “American” was becoming something distinct. These seedlings did not show the extent of this growing identity, but from this point forward, the separation of Europeans and Americans would only grow. Great challenges would emerge that tried to quell this new identity, but as we can see today, many of these early influences have filtered down to today.

Sources:

Overall

Albion’s Seed

The American Colonies

The Origins of American Slavery

New England

Mayflower

American Jezebel

Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul

New England Bound

New York

The Island at the Center of the World

Chesapeake

Colonial Maryland

A Land as God Made It

American Slavery, American Freedom

Carolina

Colonial South Carolina

Spanish

El Norte

French

The French in North America