One facet of studying history that I work hard to fight against is that events seem to snowball and lead to inevitable outcomes. The way to fight against this trap is to think of counterfactuals. For instance, if Adolf Hitler had died in World War 1 as so many young men did, would the Holocaust happen, or would World War 2 break out? Those who subscribe to the Great Man Theory of history would suggest that Hitler was a unique force of evil in the world that was able to rally Germany around the idea that they were being persecuted for being German and that the Jews were a key part of this. The opposing side may bring up the terrible inflation that was a direct result of the overwrought punishment Germany was subjected to for starting the Great War. Therefore, it was an environment just waiting for a charismatic leader to bring them back from the brink.

Personally, I don’t subscribe to either vision. I think, since humans are amazing at finding patterns, we create these narratives in order to make sense of an inherently messy and chaotic world. History is also chaotic and looking back at it from a distance can force people to miss the forest for the trees (great man theory) or vice versa (social history). I think there can be a balance that is struck by understanding that people are built by the environment they are raised in, but inherent biological traits aid or impede their journey into history.

In the most oppressive times in history, it can be seen that the vast majority of people are unwilling to risk it all to break free from this oppression. For instance, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn writes in Gulag Archipelago about the masses of people that he saw march in step on the orders of far fewer NKVD officers. He wonders what would have happened if people were willing to put it on the line:

Or if, during periods of mass arrests, as for example in Leningrad, when they arrested a quarter of the entire city, people had not simply sat there in their lairs, paling with terror at every bang of the downstairs door and at every step on the staircase, but had understood they had nothing left to lose and had boldly set up in the downstairs hall an ambush of half a dozen people with axes, hammers, pokers, or whatever else was at hand?

But he also notes that it is likely that the NKVD knew how to prevent such uprisings:

The whole system of oppression...was based on keeping malcontents apart, preventing them from reading each other's eyes and discovering how many of them there were; instilling it into all of them, even into the most dissatisfied, that no one was dissatisfied except for a few doomed individuals, blindly vicious and spiritually bankrupt.

Is it possible that one person standing up and leading the way to act against the NKVD? It’s possible, but it may not have gone very far and may have led to a further crackdown on everyone else. Were the prisoners so downtrodden that they felt it was unnecessary to risk it? Probably, but it only takes one person who has nothing to lose, right? All of this is to say: it’s complicated.

I look askance at anyone that follows any of these ideas firmly since I think they both fundamentally miss a key part of history. I also think that both of these theories create a sense of inevitability inherent in them. The great men were destined to do this by the miracle of their birth or the societal conditions at a certain moment were bound to lead to that. I think most of the time there is a counterfactual that can be proposed that undercuts these arguments. Again, humans are very good at finding patterns and building narratives. With all of that said, I think there is a single moment (at least so far in my historical studies) that was inevitable.

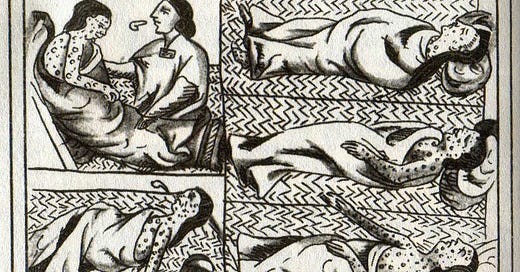

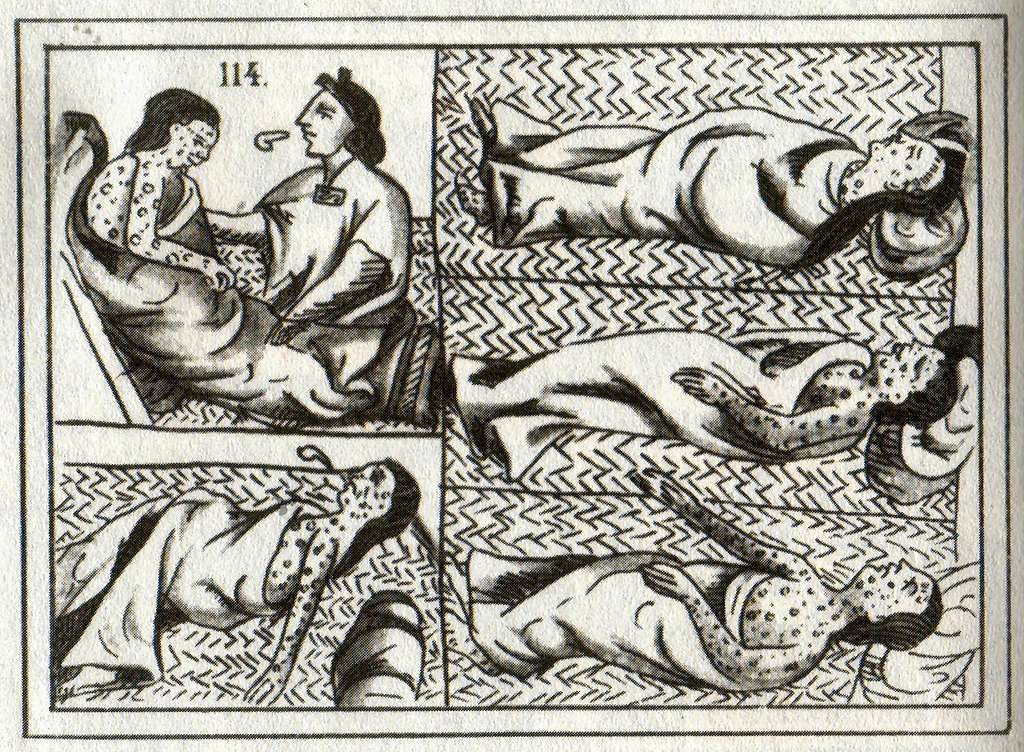

The mass death due to disease of the American natives was inevitable in my eyes. With the recent pandemic, it has become clear that biological realities still play a large role in human society, even in the 21st century. With centuries of herd immunity and exposure to viruses, decades of vaccines and medical research, and an incredible effort to slow down the spread, 7 million people are dead from SARS-CoV-2. I will not wade into the contentious waters with regard to this virus here, but I wanted to use it as a backdrop for what the American natives were faced with and why I think the outcome was inevitable.

The diseases that killed the natives, more specifically Smallpox, were exceptionally contagious and deadly, especially compared to COVID-19. In the 15th and 16th centuries, diseases were a known fact of life in Europe, though they were not well understood. Germ theory was not fully accepted until the end of the 19th century, though, there were some ideas about how to prevent the spread and treat diseases. However, prayer was often seen as just as valid as any sort of medical intervention (often bleeding, leaching, or sweating).

On the other side of the Atlantic, the natives did not have the same familiarity with disease. They still got sick, but they were often infected with parasitic diseases from food and diseases that were not nearly as contagious. They did not face the toll that the Plague and later Smallpox would put on communities. Their immune system was not prepared for what would step off those ships in 1492.

To try to counter the inevitability of this tragedy, I’ll start with some hypothetical situations.

What if the Spanish had come later? The Spanish, and much of the rest of Europe, felt as though they were facing an existential threat from the Islamic world in 1492. They had to trade with the Muslims in the Mediterranean to access those much sought-after Far Eastern spices and silks. Traveling to the west across the Atlantic to reach Japan and China directly was one of the main reasons for the Columbus voyages. The auxiliary goal of spreading Christianity to the Far East with hopes of enveloping the Islamic world was just as important. So, it is unlikely that the Spanish or Portuguese would have been willing to wait. Furthermore, the English, French, and Dutch were chomping at the bit to expand their own overseas empires. They would do everything they could to undercut their Iberian neighbors. However, let’s assume that all of the European Christians were able to settle their differences with the nearby Muslims and waited. Let’s also assume the English, French, and Dutch were unsuccessful in their attempts or were stymied by the Spanish and Portuguese.

How long would they have to wait? Well, as I stated above, the cause of disease, as we understand it today, wasn’t accepted until the end of the 19th century. Is it likely that there would have been no impetus to travel west of the Eurasian continent for another four hundred years? I highly doubt it. In that amount of time here in the real world, America was colonized, had a revolution, and fought a civil war. France had 5 more kings, went through a bloodier revolution, and was on their third republic attempt. England’s empire spanned the globe. Must I go on? Four hundred years is a long time to wait. That’s just to get to a time when germ theory is accepted. Furthermore, an even deadlier pandemic than we just witnessed is just 30 years away. Perhaps, though, the Spanish Flu would not have been as deadly due to other circumstances. We will never know. Let’s keep pushing the discovery of the Americas by the Europeans even further, shall we?

What if they made it to the modern day? We were able to roll out a vaccine for COVID-19 in less than a year, surely we could do the same for the natives if we came upon them today. Well, that’s possible, though there are some issues. We have vaccine hesitancy among those who have had successful vaccines throughout their lives. These natives we just came across do not speak our language and we have no translator. They do not understand our scientific breakthrough, what we want to do with this needle, or why we want to stab them. Perhaps we can convince them that, in the long run, this pain will help. We also must keep them separated from our germs. We can quarantine the best we know, but a hundred million people will need to be vaccinated. We’ll wear the appropriate PPE, look like space men, and jab them with needles. This operation would need to be mandatory and would likely border on unethical if it were to be conducted quickly. But, with all of that, sure it may have been possible.

But, this is also assuming that the Americas were stagnant from 1450 onward. This becomes even harder to argue when considering the possibility that the Americans may have “discovered” Europe, Africa, or Asia. If they were able to make it back to the Americas without dying on their own, it is likely that the diseases would have spread all the same.

This analysis is not an attempt to excuse or distort what happened in the New World when Spain arrived. Outside of the disease, the Spanish slaughtered or enslaved millions, pitted tribes against each other, and subjugated entire populations. Not much better could be said of the Portuguese, French, or English in the Caribbean. These efforts were deliberate and brutal. However, what was not deliberate was the death from disease. This may be a weird distinction to make, but I think it’s important. The subjugation was no accident, the absolute decimation of the American native population was.

By 1600, about 95% of the American population was dead. If the Spanish mission was to kill the entire population of a continent, then they were succeeding. But, if it was to convert the natives and create a bastion of Christianity across the ocean, it was a dismal failure. Furthermore, the enslavement of the natives to extract goods was just as much of a failure. The Spanish were hoping to use the natives for labor, not for them to all die. It is imperative that slaves remain alive, or else what use are they to the enslaver (This is a harsh truth of slave societies, as brutal as it may be). By this point though, the Spanish had given up on trying to use the natives. They turned to another market that would have just as lasting consequences. They turned to Africa.

The destruction of the American native population was a tragedy that bears few comparisons. I’m not going to tackle the question of genocide here, though, I’m sure I will someday. I struggle with this issue because usually, there are many steps that lead to a tragedy. If someone gets hit by a car you can usually talk about the speed of the car, the awareness of the driver or the pedestrian, etc. There are several ways that this could have been avoided. In the case of the massive death by disease that destroyed the Native American way of life, there are no counterfactuals. There was no single person or societal shift that could have saved them all. This was the harsh result of a biological reality. This was a tragedy that was inevitable.